|

| The job doesn't stop when the weather won't let us work outdoors. There's cataloguing, data entry, and mapping to keep us busy in the office. |

Showing posts with label Mapping. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Mapping. Show all posts

Friday, July 12, 2013

Rain Days

Wednesday, June 12, 2013

Tracking Elfshot Artifact Reproductions, Part 2

|

| Harpoon heads |

|

| Harpoon heads and art on display in Cambridge Bay |

|

| In this case, I made the whip and the dog muzzle sitting in the lower right foreground. |

Photo Credits:

1) Screen capture from 3DS Kitikmeot Portfolio http://3dservices.com/portfolio/kitikmeot-artifacts

2,3) Screen captures from Google Streetview https://maps.google.ca/help/maps/streetview/gallery/arctic/kitikmeot-heritage-society.html

Friday, January 4, 2013

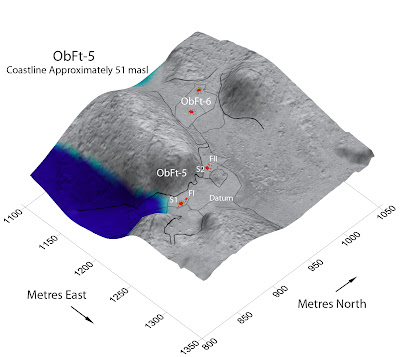

3D Air Photo Maps

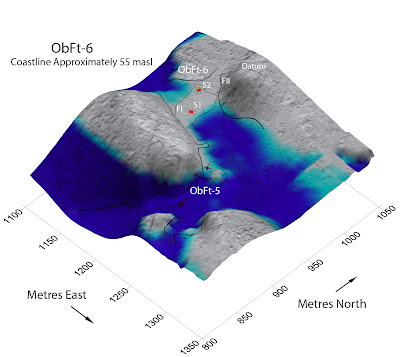

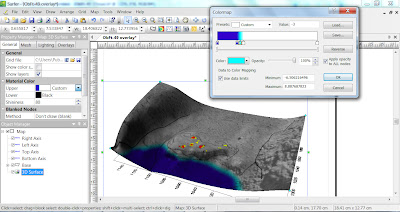

The field reports are getting a new type of map this year. In addition to the usual line drawing site maps and feature plans, I've been working on some 3D renderings that combine our field drawings, total station data and government air photos. I've been using Surfer for the past decade or so to make 3D surfaces based on data collected via total station or theodolite, but older versions of the software didn't allow raster images to be draped over the 3D wireframes. But this summer, Corey and John figured out how to combine air photo base maps with 3D surfaces.

These models give a quick visual reference of how the features in a site are arranged across the landscape and the details in the air photo give the viewer a good sense of the variations in terrain. They are turning out to be particularly useful in visualizing the past environment. The sites that we are working on have experienced as much as 50 metres of isostatic rebound since they were occupied 3 or 4 thousand years ago. Assuming that they were originally situated close to their contemporary shorelines, I can reconstruct the sea level as it would have been when the sites were occupied. A new landscape emerges - with hills separating into islands and valleys that are today half a kilometre inland becoming tombolo beaches.

Now that we know how to combine the air photo raster images with the 3D surfaces, its a relatively simple process to create these composite maps using data that was already collected in the field and prepared in the lab. To make these maps from scratch would involve a fair bit of work, but since we've collected the data and used it in other ways already, adding this step is a relatively painless way to create some attractive and informative new visuals.

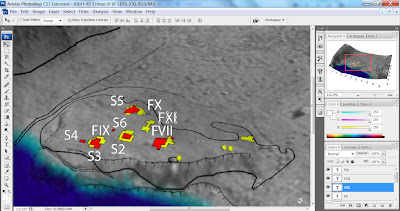

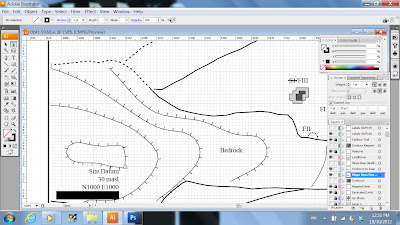

I create the skin that I want to drape over the 3D surface in Adobe Illustrator and export it as a .tiff. The units we excavate, the air photo and the lines showing the different landform boundaries exist as different layers in Adobe Illustrator, so its in that program that I have to decide what details I want to include on the surface of the map. I also need to know exactly how far north, south, east, and west the image extends from our site datum so that I can tie it into the total station data. The .tiff exported from Illustrator is used as a base map on a plot in Surfer 10. When I bring it in I need to change the image coordinates so that they match the area covered by the elevation data collected with the total station. Then I can add a 3D surface of the corresponding X,Y,Z total station data.

If all of that is done correctly, I have the basic map done and then its just a matter of playing with different shading and colouring options. I can rotate the model and find the best view to illustrate the site. The sea level is simulated by manipulating the material colour of the 3D surface. Surfer has some built in editing options, but I usually find the view that I like and export it as a .tiff again and use Adobe Photoshop to add the final labels to the image. I'm trying to keep the labels to a minimum to avoid clutter and help with the visual impact. The reports have many other clean, square site and feature maps to show details and precise measures and distances.

Photo Credits: Tim Rast

|

| These are not models - this is John and Corey solving a problem with knives. |

|

| As the land emerged, the sea level fell and ObFt-6 was probably a less attractive place to camp, compared to the new beach around the corner at ObFt-5. |

|

| Lori collecting location and elevation data with the Total Station |

|

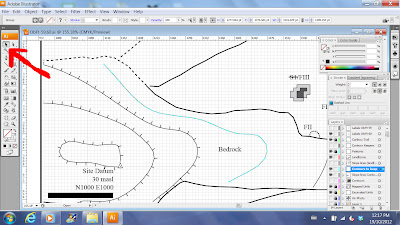

| The air photo and map data come from existing layers in Adobe Illustrator |

|

| The air photo and 3D surface are combined in Surfer. In the floating window, I'm adjusting the colour and shading to indicate what the coastline may have looked like when the site was occupied. |

Photo Credits: Tim Rast

Friday, October 19, 2012

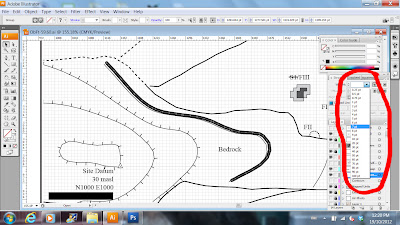

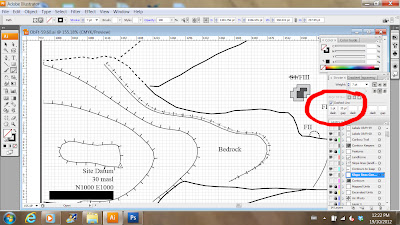

Putting Tick Marks on Contour Lines

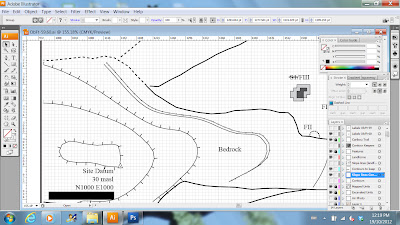

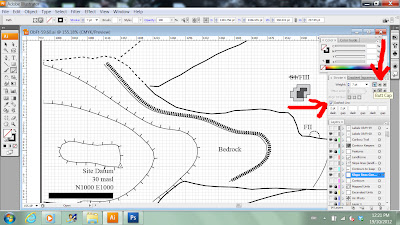

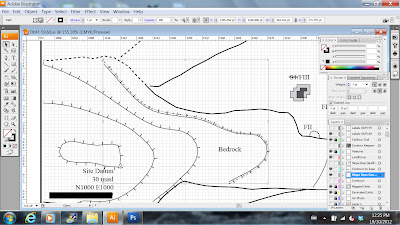

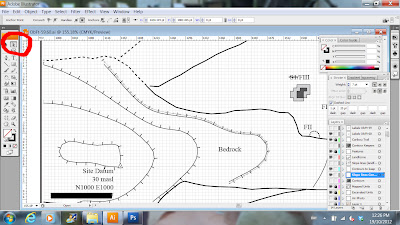

You know those little tick marks that you put on contour lines to show the direction of slope? Here's a confession, every year for the past 15 or 20 years, I've been adding those lines to maps individually, one at a time, with Photoshop or Adobe Illustrator I'd draw one tick mark and copy it a bunch of times and then rotate and place each one manually. Maps made at the end of the day or later in the week had fewer and fewer tick marks spaced wider and wider apart. But not anymore, here's a trick to make those tick marks perfectly consistent and much simpler. I'm using Adobe Illustrator in this example, but it should work in any vector graphics program that lets you make dashed lines. (click on the images to make them bigger)

|

| Change the weight of the line. You can make it any weight you want - the thickness of the line will be the length of your tick marks. I made my 7 points. |

|

| To create the individual tick marks, change the spacing of the gaps and dashes. I like using 1pt for the dashes and 20 pts for the gaps. |

|

| That's it, its done. On a simple line this takes a few seconds. On a complex line, it might take a few minutes. |

Photo Credits: Screen Grabs from Adobe Illustrator

Wednesday, October 10, 2012

Mapping Again

|

| Lines and labels from the paper map overlying the air photo. |

|

| This layer has contour lines created from elevation data collected on site using a total station. |

Monday, January 16, 2012

I love it when a plan map comes together...

It looks like I'm finally through the worst of the mapping. I finished up the last of the 79 site and feature maps required for the report this afternoon. I still need to print them out and see if they work on paper, but I'm almost done with building the pieces of the report and sticking them in place. After that it should just be editing it all together and then booting it out the door.

The artifacts are all labelled, although I need to take a few more photos of them and make sure that everything is organized and ready to send off for curation at the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre in Yellowknife. Those few photographs should be about the last pieces that I need to build the report. From then on, it will just be organizing and editing.

Photo Credits: Tim Rast

The artifacts are all labelled, although I need to take a few more photos of them and make sure that everything is organized and ready to send off for curation at the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre in Yellowknife. Those few photographs should be about the last pieces that I need to build the report. From then on, it will just be organizing and editing.

Photo Credits: Tim Rast

Wednesday, January 4, 2012

Back at my Desk

|

| More maps... |

|

| The maps have deeper stratigraphy than the sites |

A friend sent me this picture of me in the field. Somehow the fieldwork makes all this report writing worthwhile. I forgot how protective I get of my lunch during the summer.

|

| Once its in the thermos, its my coffee. |

Photo Credits:

1,2: Tim Rast

3: Claire St-Germain

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Building Up Site Plans

|

| Illustrating the layout of the site |

|

| Each little square in the grid is 1 x 1 m, and each heavier square is 10 x 10m |

|

| A tent ring and two 2x2m units |

|

| On this layer I'm adding some radial information. I have the angles and distances recorded to each test pit from the southwest corner of the tent ring we excavated. |

|

| Luckily we have some hi-res air photos of the area |

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

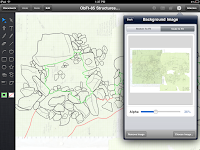

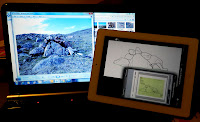

iDraw Archaeological Features on the iPad

|

| Tracing Rocks in iDraw |

|

| The green insert shows the scanned paper map |

|

| A photo of the feature, iDraw profile, source .jpg |

|

| This took less than an hour to trace |

|

| Stylus improves accuracy |

|

| I find moving file with Dropbox simplest |

Photo Credit:

1,5: Lori White

2-4,6: Tim Rast

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

I'm an excellent tracer

|

| On Screen Digitizing |

|

| Lori mapping a 1 x 1m unit |

|

| Binder full of Unit Plans |

|

| The tent ring s starting to take shape |

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

Open Street Maps for Garmin GPS

In a few hours, I'll be on a plane heading to Bilbao, Spain. We spend a bit of time in Spain's Basque Country before starting a cave and wine driving tour of southern France. We booked the car a couple weeks ago and I promised to provide the maps so we wouldn't have to pay extra for an on-board GPS. I said that I'd bring my Garmin GPSmap 62s loaded with all the maps we'd need. Then I forgot about it.

I started looking for the maps a few days ago and quickly ruled out buying them - the official Garmin Topo maps of Spain and France are over $600 US. I didn't really want to pirate them, but while searching some of the back alleys of the internet I found out about OpenStreetMap, which is a kind of cartographic wikipedia. There are a few ways to play with and download the maps on OpenStreetMap itself, but to get them onto your Garmin GPS you need to checkout another site called: Free routable maps for Garmin brand GPS devices (garmin.openstreetmap.nl). Which is free and awesome.

The interface on garmin.openstreetmap.nl is simple and the instructions are easy to follow. To select the maps you want all you have to do is highlight them on the big blue map of the world. You can pick one tile or several. When you have the maps selected all you need to do is enter your e-mail address and click "Build my Map". Your map request is added to the queue and you are sent an e-mail with a link to check on its progress. I've used it twice and the first map set was supposed to take an hour or so to build and it was actually done in about nine minutes. My second map took closer to the promised hour. When your map is ready to download you are sent a link with several download options. I picked the "Installer for Garmin Mapsource" option and it took 5-10 minutes to download my map and another 5 minutes to install it. When it was installed I could add it to my GPS from Mapsource or Mapinstaller.

The resulting map looks great. I haven't had a chance to ground truth it yet, but in Mapsource, it looks as good or better than the $600 Garmin product. However, I did notice that when I downloaded and installed a second set of maps it overwrote the first set that I'd download, even when I changed the folder name. If someone figures out a way to fix or avoid that, I'd be grateful. Even so, I'm definitely keeping Free routable maps for Garmin brand GPS devices (garmin.openstreetmap.nl) in my bookmarks.

Photo Credits:

1) Tim Rast

2) Screen grab from garmin.openstreetmap.nl

3,4) screen grab from Mapsource on my computer.

I started looking for the maps a few days ago and quickly ruled out buying them - the official Garmin Topo maps of Spain and France are over $600 US. I didn't really want to pirate them, but while searching some of the back alleys of the internet I found out about OpenStreetMap, which is a kind of cartographic wikipedia. There are a few ways to play with and download the maps on OpenStreetMap itself, but to get them onto your Garmin GPS you need to checkout another site called: Free routable maps for Garmin brand GPS devices (garmin.openstreetmap.nl). Which is free and awesome.

|

| Selecting an area around Bordeaux |

|

| Free OpenStreetMap from garmin.openstreet.nl of Bordeaux, France. |

|

| The same area from Garmin's TOPO France v.2. Not free, at all. |

Photo Credits:

1) Tim Rast

2) Screen grab from garmin.openstreetmap.nl

3,4) screen grab from Mapsource on my computer.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)